Blog by Monalesia Earle, PhD (she/her)

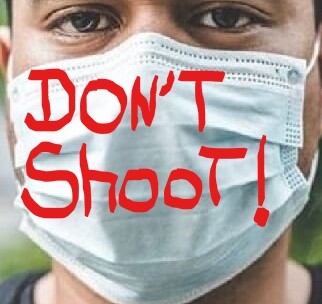

The above image of a black man wearing a face mask with ‘Don’t Shoot’ written on it is an unnecessary, yet visceral reminder to people of colour that wearing a mask in the time of COVID-19 is likely to get us profiled, arrested, or even killed but I will come on to this later.

Communities of colour are disproportionately at risk of falling ill or dying from exposure to COVID-19.

Why?

We know that inequalities in BAME communities abound and the prevalence of comorbidities increases our risk of being disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. We suffer more from diabetes, heart disease, stress, obesity, hypertension and asthma, than our white counterparts. These conditions lead to weakened immune systems, which in turn set up a perfect storm for COVID-19’s opportunistic assault.

We also know that people of colour do not accumulate wealth at the rate of our higher earning white counterparts, which makes it difficult to break out of cycles of poverty. We are less likely to own property, send our children to better schools, save for retirement, obtain bank loans to set up businesses, qualify for lines of credit, or any of the other myriad opportunities that are open to those who control access to these resources.

Furthermore, people of colour are more likely to live in densely populated areas where factories have been built and robust filtration systems have been bypassed in order to boost corporate profits. As a result, poor air and water quality further exacerbate our already dismal health outcomes. Social distancing and/or working from home is also more difficult for those who live in overcrowded housing estates and who do not have the financial resources to weather out this pandemic.

Other contributory factors that accelerate the spread and deadliness of COVID-19 in communities of colour are:

- lack of access to adequate health care

- unemployment or low wage jobs that do not allow for the building up of savings

- over-representation in prison populations which also makes social distancing impossible

- lack of access to fresh, nutritious food

All of the above factors are bound up in historical and systemic racism that has positioned the most vulnerable in society to be the hardest hit. Numerous studies regarding discriminatory and racist practices that disproportionately target communities of colour, bear this out.

In the city of Chicago (and similarly grim numbers can be applied to BAME communities in England) African Americans comprise 30 percent of the population but account for 70 percent of all coronavirus cases. And while COVID-19 does not discriminate, it is ironic that in the city of Milwaukee, health officials believe the virus was ‘introduced to the city after its first infected resident came in contact with someone from an affluent, white suburb nearby’.

When we think about comorbidities and race in the UK, and how this complicates protection from COVID-19 for communities of colour, recent research shows that:

“African Caribbean people have higher prevalence of high blood pressure, and South Asian people (particularly first generation) have higher prevalence of Coronary Heart Disease (British Heart Foundation). South Asian people are up to six times more likely to have Type 2 diabetes (Diabetes UK). African Caribbean, South Asian, and people of Mediterranean origin are also more likely to have Sickle Cell Disease, which is one of the conditions identified by the NHS as being at highest risk of mortality relating to COVID19”

(source: Race Equality Foundation)

So, while some people from upper socio-economic backgrounds are able to reside in gated communities, travel to far-flung vacation spots, dine in fine restaurants, and generally keep their distance from those who are not in their social circles, complete social distancing from the ‘have nots’ is difficult to achieve. Even the more affluent in our society rely on trains and taxis to get around, restaurant staff to prepare their meals, bin collectors to keep their neighbourhoods free of trash and infestation, news agents who sell them financial magazines that remind them of their good fortune, the invisible porters and maids who attend to their comfort at luxury hotels, and even BAME GPs (several of whom have recently died from the virus), to attend to their health. This article provides interesting further reading.

Wear a mask, save lives!

The optics of this virus cannot be underestimated. On the surface, the advice to wear masks seem to be both innocuous and important. Health and government officials suggest that wearing masks can help slow the spread of the virus, and we all want to do our part to help ‘flatten the curve’ and save lives. Yet there is another component to this advice that means something entirely different to most people of colour. Wearing a mask in public can get us arrested or killed, and here we go back to the ‘Why?’

Racist systems hold that black people cannot be trusted and that we are always up to some nefarious deed. We are therefore profiled and arrested at higher rates than whites, and painful experience has taught us that any advice we follow is understood to be through a white-centric lens, which means that it is not necessarily for our benefit or protection. So, are masks deadly or protective? It depends on who you ask.

Franz Fanon famously noted that in a white-centric world, men of colour come across certain difficulties in the ‘development of his bodily schema’. His awareness of his body is ‘solely a negating activity…a third person consciousness [it is a] body surrounded by an atmosphere of certain uncertainty. In other words, if as a person of colour I wear a mask in public and the white-centric view of the world perceives me to be a threat, then would not wearing a mask in public put me at equal risk of arrest for not following the rules?

The purpose of this blog has been to start an important conversation on expectations of safety when safety has never been assured in communities of colour. It is meant to get us thinking on a deeper level about the challenges in communities of colour that have existed throughout time and will continue to exist even when the COVID-19 pandemic becomes yet another tragic footnote in history.

I end this blog by drawing attention to @tezilyas hashtag, #YouClapForMeNow. It is a powerful reminder that the people who are now being asked to put their lives on the line to save those who may have ignored or excluded them in the past, have always been there. Perhaps you simply forgot how to see them.