On the 15th of October, this story broke in the media with the shocking headline “Sharp rise in babies facing being taken into care”. It concerns the latest findings of the Nuffield Family Justice Observatory (NJFO) “Born into Care: new-borns and infants in care proceedings in Wales” showing that new-born removal in Wales has doubled since 2015. The research team from Lancaster and Swansea Universities was led by Professor Karen Broadhurst and utilised data from Cafcass Cymru.

What is particularly interesting about these findings is that, whilst they mirror earlier research published in 2018 in respect of new-born removal in England, they highlight differences between the two countries, despite each working to the same legal framework; the Children and Families Act 2014.

What is particularly interesting about these findings is that, whilst they mirror earlier research published in 2018 in respect of new-born removal in England, they highlight differences between the two countries, despite each working to the same legal framework; the Children and Families Act 2014.

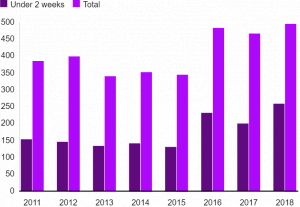

“Born into Care: new-borns and infants in care proceedings in England” published by the NFJO in October 2018 found the likelihood of new-borns in the general population becoming subject to care proceedings had more than doubled, increasing from 15 new-borns per 10,000 live births in the general population in 2008 to 35 per 10,000 in 2016. The graph (Source: NFJO) demonstrates a similar rise in Wales.

New-born removal

Removing a baby at birth is generally seen as being a “last resort”; where the vulnerable new-born is at immediate risk of significant harm. Indeed, the report describes it as “perhaps the most difficult, and brutal, decision that professionals can make to intervene in family life”.

If a baby is at risk of immediate harm, there aren’t many people who would disagree that that infant must be kept safe, no matter how painful this separation will be for the whole family. Babies are removed from mothers sometimes hours after their birth to do just that. More often, mothers are kept in hospital with their baby until a court hearing can be listed so that a judge may make the decision on whether removal is necessary. Mothers are then asked to attend that hearing, perhaps giving oral evidence if they disagree with the removal of their baby. In 2018, 83 babies in Wales were removed within two weeks of birth (a figure that has risen from 39 in 2015). On each occasion it is possible, even probable, that the mother attended a hearing for an application for an interim care order (ICO), very soon after giving birth.

A harrowing account by a mother who had her new-born baby removed (and then ultimately returned) can be found here. It details how the mother, still physically recovering from the birth of her child just a few days earlier was required to attend court and argue her case against separation.

A harrowing account by a mother who had her new-born baby removed (and then ultimately returned) can be found here. It details how the mother, still physically recovering from the birth of her child just a few days earlier was required to attend court and argue her case against separation.

This alone raises many questions around the mother’s capacity to be able to engage in a court hearing so soon, whether it is right that she should do so given what the World Health Organisation tells us about maternal mental health. Are we expecting too much from mothers? Should it be that, unless there is an imminent risk of harm, that this key developmental time for both baby and mother is protected?

The Royal Free Hospital, in developing a standardised pathway for vulnerable babies at risk of separation from their mother (usually as a result of the need for medical intervention as opposed to any legal applications) states:

“Separating babies from their mothers after birth has long-term detrimental effects on breastfeeding, mother-baby attachment and mothers’ mental health.”

This is further emphasised in vast numbers of research on the matter detailed here by Unicef, on the importance of skin-to-skin contact (both maternal and paternal), “kangaroo care” and breastfeeding.

The Legal Framework

The grounds for making an ICO are found under Section 38 of the Children Act 1989. The court must have ‘reasonable grounds’ to believe that the baby or child has suffered (or is at risk of suffering) significant harm and that this is as a result of care provided by parents falling below a reasonable standard. The “threshold” for removal of a child under the auspices of an ICO is generally regarded as lower than that of a more permanent order, such as care and placement orders, or special guardianship orders. It’s often seen as a “holding position” whilst further assessments are undertaken to make a final decision on where a child should live and who he or she should have contact with.

In the case of L (A Child) [2007] EWHC 3404 (Fam), Ryder J made a number of observations regarding the issue of immediate removal (not, in this case, of a new-born). He said:

- “In approaching the issue of interim removal, the court must consider whether there is an imminent risk of really serious harm ie whether the risk to the child’s safety demands immediate separation”

- “If there is no such imminent risk, the question of a parent’s ability to provide good enough long-term care is a matter for the court at the final hearing and should not be litigated at an interim stage, effectively prejudging the full and profound trial of the LA’s case and the parents’ response”

- “Professionals must take great care not to conflate the issues of the test to be applied to the issue of removal (an acute safety question necessitating the child’s removal) and the nature and extent of the risk of harm (which will only justify removal unless it is an imminent risk of really serious harm, not just a heightened perception of risk as evidence emerges if that risk can be contained by adequate arrangements).”

This case was 12 years ago. So why are we seeing such vast increases in the removal of new-born babies from their parents?

The impact of austerity and the “Baby P” effect

In the “Born into Care” research, Professor Karen Broadhurst is quoted as saying “all sorts of factors” could help explain the increase, including cuts to services;

In the “Born into Care” research, Professor Karen Broadhurst is quoted as saying “all sorts of factors” could help explain the increase, including cuts to services;

“Certainly work that has been done by other researchers suggests that austerity and the cutback in preventative services is impacting overall on the numbers of children coming before the family courts in care proceedings”.

This recent article by Patrick Butler explains the decimation of services by government for some of the most vulnerable families. Cuts of 62% to early years service spending by local council has meant an enormous reduction in the numbers of families able to attend SureStart Centres after up to 1000 of them have been closed down since 2010.

Between April 2018 and March 2019, a record number of 1.8 million people used food banks, many of them families living in poverty and many falling foul of the “five week wait” for Universal Credit.

The “Baby P effect” is often quoted as a factor for the rise in care proceedings and is a phenomenon more widely discussed in this Community Care article and Dr Ray Jones’ book “The Story of Baby P”.

Jacqui Gilliat, a barrister at 4 Brick Court and general editor of Family Law Week Blog also touches upon the “Baby P effect”:

“There is already hard data to suggest that the incidence of issuing proceedings is on the rise again and I would venture to suggest that there will be more applications for interim removal by local authorities, whether this is justified or not by the evidence, and a tendency to put the onus of decision making on the courts. One can easily see why local authorities will be tempted to take the line, if in doubt, issue.”

(Source: Family Law Week)

Essentially, it’s said that lawyers are in favour of “issue now, ask questions later”, social workers are now “fire-fighting” and families now are “paying the price” since the horrific abuse and subsequent sad death of Peter Connelly at the hands of his family.

So, what does this all mean? Can it be that, since 2015, parents in Wales have suddenly become twice as deficient in their parenting so as to be deemed not “good enough”, and removal of their new-born sought? Or are there other issues at play? Do poverty and austerity play a role? And what of the “Baby P effect”?

Your thoughts are very welcome.

The Strengthening Practice Team

Pictures taken from Flickr Creative Commons with thanks:

“Baby feet in mother’s hands” Olga

“Food Bank” The JH Photography