It is a truth universally acknowledged that January is a tight month; the cost of Christmas leaving most of us with modest sums in our bank accounts and even less in our pockets. It’s a time of indulgence and treats and family time; meals together and outings. Many of us are off work, the children are all off school and there are only so many pyjama days you can have before you go a bit stir-crazy and end up in some godforsaken soft-play, or at the park (often no longer a “free activity” given the careful and thoughtful positioning of ice-cream vans and cafés selling tea and cakes).

It is a truth universally acknowledged that January is a tight month; the cost of Christmas leaving most of us with modest sums in our bank accounts and even less in our pockets. It’s a time of indulgence and treats and family time; meals together and outings. Many of us are off work, the children are all off school and there are only so many pyjama days you can have before you go a bit stir-crazy and end up in some godforsaken soft-play, or at the park (often no longer a “free activity” given the careful and thoughtful positioning of ice-cream vans and cafés selling tea and cakes).

Let’s be honest, by the time everyone gets back to work, the majority of us are looking wistfully towards the end of the month so we can pay the bills and eat normal meals, instead of using up the Christmas food shop and presents by eating cheese for breakfast and Ferrero Roche for tea.

But what do you do if you have no payday to look forward to, or plan for? How do you feel about the children going back to school if you’ve struggled to feed them over Christmas, or if you’ve had no money to take them anywhere? What if you are one of the 14.3 million people living in poverty in the UK?

Measuring Poverty – Recent Developments

-In December, the Royal Statistical Society revealed its ‘statistics of the year’ for 2019, with the “winning” UK statistic relating to the extent of in-work poverty in the UK. The Institute for Fiscal Studies exposed the proportion of those in relative poverty who live in a working household as 58%, demonstrating the scope of poverty as an issue affecting those dependent on the welfare state as well as those in employment. I find this quite a shocking statistic but hope it challenges the narrative around the correlation between poverty and being on benefits.

-An article published on the day of the general election last month held the headline “UK child poverty rate could increase under current government”. It looked at the real-world impact of the three key political manifestos: The Conservatives, Labour and The Liberal Democrats. Of course, I don’t need to tell you what happened on the 12th of December, but the article makes for interesting, if not, chilling reading.

-The Child Poverty Action Group, a registered charity who have been in existence for over 50 years published their own manifesto for ending child poverty in November 2019. We can but hope that this is carefully scrutinised by those in power as a comprehensive dissemination of the current issues and some practical, helpful solutions.

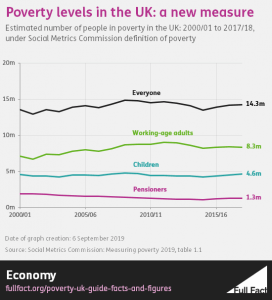

-The UK’s independent fact checking charity, Full Fact, looked at the Social Metrics Commission (SMC) who produced a report in July 2019 entitled “Measuring Poverty” from which is taken the graphic below. Full Fact (whose own information on poverty can be found here) describes SMC as “one of the most comprehensive measures of poverty on offer at the moment”.

-Last month, the SMC produced a piece of work: “Equivalisation in Poverty Measures Report” in which is described “the process through which many poverty measures account for the variations in needs of families of different sizes and compositions”. This is important because what poverty “looks like” to me as a married, working mum of young children is very likely to be different to how a single, homeless mum of young children in receipt of benefits may measure poverty. I know this because I’ve been both.

Some of the key findings of the SMC report include:

Some of the key findings of the SMC report include:

• 22% of the population are living in poverty

• Poverty rates among children have risen from 31% in 14/15 to 34% in 17/18.

• 31% of those in poverty – 4.5 million people – are more than 50% below the poverty line

• 48% of people in poverty live in a family where someone is disabled

• 46% of families with a Black head of household live in poverty, compared with 37% of families with an Asian head of household and 19% with a White head of household

So, immediately, I can see that you are more likely to live in poverty if you are a disabled child with a Black head of household. The question is why? Why should black and ethnic minorities or disabled people be at a disadvantage?

What is also evident from the graphic is the level of “persistent poverty” that exists. In fact, the report states that 49% of those in poverty have been so for at least two out of the last three years. This equates to 11% of the whole population (around 7 million people) in “persistent poverty”. The question is why? Why is it so difficult to get out of poverty once you’re in it?

“The poverty figures you’ll often seen quoted are also usually ‘snapshots’ – they show how many people are in poverty at a given time. That’s only part of the story, because poverty is a temporary experience for some and a long-term situation for others. So, it also helps to look at measures of persistent poverty which picks out people who’ve been in poverty for long periods.”

(Full Fact)

The whole picture?

The statistics in the SMC report are both shocking and disheartening – but I don’t think they tell the whole story.

Poverty is defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as “the state of being extremely poor”. Perhaps in the novels of Dickens or Hardy, that may well be true. But in recent years, poverty has taken on a more ‘multi-faceted’ definition. For example, as the SMC report has demonstrated; you can be employed and have a home but still be defined as living below the poverty line.

Poverty is not always just about your income, either. It’s now recognised that families have different costs to pay out, such as childcare or the costs associated with a disability, but that they also have different levels of savings or assets to draw upon.

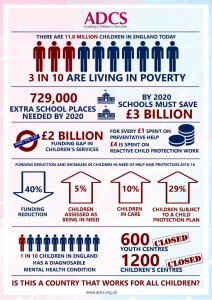

There are further layers of poverty which are being recognised and understood more. In October 2017, the Association for the Directors of Children’s Services (ADCS) published a position paper: “A country that works for all children”. In this paper, ADCS points out the sheer volume of children living in poverty at that time – 4 million – and that England had no child poverty reduction strategy. The paper referred to the Institute of Fiscal Studies prediction that by 2020/21 five million children would be living in poverty.

However, the ADCS paper did not confine poverty simply to a family’s financial situation:

“We know that family income has a causal relationship with poor child outcomes, but poverty is not only measured in financial terms. Many children, young people and families also find themselves experiencing poverty of access to opportunities. This can take many forms, including children with additional needs being squeezed out of mainstream school to those living in rural areas having limited access to essential public services e.g. youth centres and libraries.

This inequality of access does nothing to support the social mobility agenda.”

(ADCS October 2017)

Of course, financial poverty and poverty of access to opportunities for families can exist in isolation, but it’s more likely that if you experience one, you experience the other. If, like I once was, you are a single, homeless, isolated, unemployed mum of young children, you are going to find it much more difficult to participate in “life” than if you were financially comfortable, had a home and a rich network of support. The link between poverty and social exclusion, or isolation is one that cannot be underestimated.

The decimation of services

Another important point raised in the ADCS paper is how poverty has increased and access to opportunities have decreased as a direct result of the government’s assault on support services for families.

Back in the early 2000’s, I lived on a council estate, on benefits and was single-handedly raising my children. All around me, everyone had nothing. Many were single mums, like me, struggling to get by on benefits. We all became, and have remained, good friends.

The one shining beacon on our estate was our local Sure Start Centre where we all first met. There, you could take your children to play sessions, you could take courses whilst your children were cared for in the creche; parenting courses, cookery courses, budgeting, job club – everything designed to improve the life chances of your family and your overall quality of life. There was a Health Visitor who would regularly visit, Midwives often held their ante-natal checks and classes in the centre, and there was an on-site social worker. I can only speak for myself, but I never felt threatened by the presence of these professionals because they were all part of one team – and I was part of the same team. We all wanted the same things for our families. It was a support network I will never forget and always hold dear.

When my local authority announced in January 2016 that it proposed to close all but one Sure Start centre, I got involved in the campaign against it. I met with senior managers and they explained that they were tasked with saving £53 million from their budget. It was also explained to me that many of the Sure Start centres were located in between areas of high deprivation, and high affluence. As such, the more affluent parents were using the Sure Start centres for cheap childcare whilst they worked. Because of government cuts, this was simply not sustainable and within months almost all of our Sure Start centres closed down. I was devastated. I had moved on in my own life; having managed to take myself off benefits and into self-employed work and finally out of the “persistent poverty” which had plagued my family for well over a decade. However, I knew that there were so many vulnerable families who would really suffer at the loss of these services. Where there had been support work undertaken, there would now be, potentially, reactive work undertaken. Not only does this put additional strain on families, but it also stretches social work and limits the resources to go around. Social workers would be “fire-fighting” whilst families struggled further.

Our story is not unique. This graphic by ADCS clearly demonstrates the absolute decimation of support services.

The rise in families living in relative poverty, the rise in poverty of access to opportunities and social exclusion and the rise of government cuts to our social care services creates what can only be described as a perfect storm for some of our country’s most vulnerable children and their families.

“Poverty constrains people’s opportunities, only through collective actions can we drive change to achieve a country that works for all children. The lack of sustainable funding for children’s services, including schools, must be addressed as a matter of urgency.” (ADCS October 2017)

Without wishing to preach to the converted, poverty is our collective responsibility as a society. Whilst we can’t change government policy and are limited to what we can achieve nationally, if we can help at a grass roots level, it is unquestionably the right thing to do.

Your local food bank can be found here and are always deeply appreciative of any and all donations. You can also find food bins at almost all larger local supermarkets where you can donate to the food bank whilst doing your own shopping.

Your local shelter can be found here and donations of blankets, coats and clothing and toiletries are very much welcomed.

Together, we can do more.

Strengthening Practice donates to both Crisis and Shelter. If you want to do something fun and healthy this April to combat poverty see Shelters Home Run Challenge and consider joining in – we are!

Thank you for reading.

Annie

Social Care trainer

Strengthening Practice

annie@strengtheningpractice.co.uk

Image by Frantisek Krejci from Pixabay – thank you.