Last week, we brought you a Social Toon by Jo Fox entitled “The Cycle of Change” which delved into Prochaska and DiClemente’s Transtheoretical Model of Change. An important point raised during the animation was that this model relies upon change being within your gift. In this week’s Blog, I’m going to be exploring what happens when structural, psychosocial and systemic inequalities mean it becomes very difficult to make and sustain change, particularly within the context of child protection. Parents are expected to make changes to ensure their parenting is “safe” and “good enough”, but just how possible is that? Do we ask too much?

Last week, we brought you a Social Toon by Jo Fox entitled “The Cycle of Change” which delved into Prochaska and DiClemente’s Transtheoretical Model of Change. An important point raised during the animation was that this model relies upon change being within your gift. In this week’s Blog, I’m going to be exploring what happens when structural, psychosocial and systemic inequalities mean it becomes very difficult to make and sustain change, particularly within the context of child protection. Parents are expected to make changes to ensure their parenting is “safe” and “good enough”, but just how possible is that? Do we ask too much?

What does change mean to you?

In order to better understand the inequalities which may impact upon the changes parents are asked to make, you need to begin by asking what change means to the person you are asking to make it.

Consider your own personal life for a moment; are there aspects in which you would benefit from making changes? What would be the impact upon you if you made those changes?

As Jo said in her animation, repeated behaviours, whether healthy or unhealthy, give us something that we presently can’t or don’t get anywhere else. For example, a parent may drink excessively to escape their own damaged or abusive childhood. If this parent hasn’t learned another way of dealing with their abuse, asking them to simply stop drinking is unrealistic and relapse is almost inevitable. It makes sense then to try to address the reason behind the pattern of repeated behaviours before expecting any meaningful and sustained change, even when the stakes are as high as they are in child protection.

The impact of the change itself also must be considered. There are huge benefits to this family if the parent stops drinking; the child/ren will be safer and possibly better cared for, adult relationships will improve, the home environment (if affected) may get better and the family’s finances will increase. However, if there has been no scaffolding around the parent to help them make the change, or they have no healthy alternative to drinking excessively, or the reason for the drinking has not yet been uncovered, all of these aspects may instead deteriorate, heightening the risk and instead worsening the family’s situation.

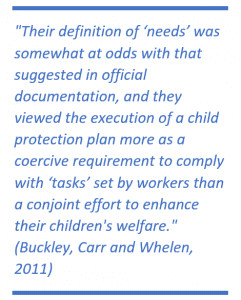

These seem like very obvious points, but we know from research that parents don’t always understand or agree with what needs to change, why things need to change and the consequences of action or non-action (Smithson, 2015). Parent’s perception of “needs” in their own family also often differs from that of professionals, so there is a further disconnect (Buckley, Carr and Whelen, 2011).

The Passage of Time

I think most people would say they were a very different person ten years ago to what they are today. I’d say it’s a reasonable statement to make that as you get older, some of your priorities, standards and beliefs may change simply through the passage of time, maturation and personal development. What makes you tick at 20 is probably different to what makes you tick at 30. I’d go so far as to say that sometimes even your moral compass shifts and the way in which you deal with difficulties can change. The changes we make within our lives can be heavily influenced by the resources we have, or do not have, around us, but social factors and our own behaviours can also help to decide whether we make changes, or not.

I think most people would say they were a very different person ten years ago to what they are today. I’d say it’s a reasonable statement to make that as you get older, some of your priorities, standards and beliefs may change simply through the passage of time, maturation and personal development. What makes you tick at 20 is probably different to what makes you tick at 30. I’d go so far as to say that sometimes even your moral compass shifts and the way in which you deal with difficulties can change. The changes we make within our lives can be heavily influenced by the resources we have, or do not have, around us, but social factors and our own behaviours can also help to decide whether we make changes, or not.

Looking back on myself ten years ago at the age of 30, I was indeed a very different person. I grew up in an abusive family and entered the foster care system, having a poor experience there too. When I fell pregnant at the age of 16, my foster carer threw me out and I was put into a hostel by my corporate parent. I really had no one to guide me and teach me helpful ways to behave; I was very alone and isolated. By the age of 30, I had five children to four men, all but one of whom had abandoned me during my pregnancy. I was a good mum physically, ensuring my children were always well looked after and my home was clean and warm, but emotionally parenting my children was alien to me. I had tried really hard to make my way in the world, staying off benefits as much as possible, working and undertaking distance learning to improve my education so that I would be a good role model for my children, but, ultimately, I found life very difficult and unpleasant. I reacted quickly and hot-headedly to disappointments and difficulties; the end of a relationship being a huge trigger for me. I was unable to cope with the sheer enormity of rejection and would often self-harm. Everything came to a head when I was 32 and I tried to take my own life, not for the first time. My local authority, who had accommodated my children on two prior occasions at my request, stepped in and initiated care proceedings.

At that point, my whole world imploded. I lost my children, my home, all of my benefits and many of my friends. Yet, I also had the realisation that I really needed to make changes within my own life to be a ‘good enough’ parent to my children, and that included learning new skills and behaviours through therapy.

I was up against it. How do you make changes when you’re cold, hungry, homeless, living without your children, unable to participate in society, have low access to resources and when all you’ve ever known is to react? And how do you prove that you can sustain these changes in the context of care proceedings?

Capacity to change?

In 2015, an article was published; “Assessing parental capacity to change: The missing jigsaw piece in the assessment of a child’s welfare?” (Platt D & Riches K). Described as “a framework for assessing parental capacity to change, for use by social workers when a child is experiencing significant harm or maltreatment”, the article seems to direct the responsibility for change solely on the parents:

“In circumstances of such harm, to keep a child in his or her own family safely, the parents must resolve the problems that led to the children being at risk in the first instance, and generally do so through positive engagement with services” (p.141).”

How do you meaningfully engage with a service that is telling you that you are not a “good enough” parent, or that uses its power to demand you engage with other services lest you lose your children forever? Must you simply smile and comply? What if you comply too much?

Furthermore, what do you do if the “services” that you need are physically inaccessible to you? How do you get to a support group if you have no money for bus fare?

How do you change the way that you react or respond to situations when you’ve not had the benefit of nurturing relationships with family or partners? How do you access therapy or counselling in good time when you, like everyone else, are at the mercy of waiting lists and cuts to services and resources?

And what of power? How does power fit into the cycle of change?

This quote is taken from the 2011 article ‘Like walking on eggshells’: service user views and expectations of child protection (paywall – apologies) and gives a compelling insight into the role power plays when it comes to parents making changes in the context of child protection. Are parents authentically invested into changing their own damaging behaviours to better improve their children’s lives? Or are they simply following a script of compliance? How do you as a social worker tell the difference? And what could you do to better even out the power dynamic?

But ultimately, how do you do all of this if you’re separated from your children and grieving their loss? And how on earth do you demonstrate all of this within 26 weeks?

And what about the children in the middle?

The voice of the child

Generally speaking, I think it’s widely agreed that it is considered better for children to remain within their birth families where it is safe to do so. It is the ethos of the Children Act 1989 and the guide to with which most social workers work. Of course, there are exceptions and where there are changes to be made, sometimes parents do need to be separated from their children whilst they make those changes, for the child’s safety. Sometimes the separation itself can be the catalyst for change.

And, whilst foster care can be a truly favourable option for some children, when parents are separated from their children, it can create another layer of difficulty when a parent is trying to change past or current behaviours. I know first-hand how hard it is to survive without your children day in, day out, and sometimes just navigating that itself is enough for some parents. Sometimes, there simply isn’t enough “headspace” to then go on and make changes, or the changes themselves could be superficial and motivated by the deep desire to have their children back at home.

I abhor the word “timescales”, but cannot deny its relevance. I don’t think children can wait around indefinitely, either in potentially unsafe environments at home, or in potentially insecure placements, whilst their parents make changes, however much they may want to. But I also don’t think children should be separated from their families unless there is a really serious risk of imminent harm. There’s a fine balance to strike, as those who do this job every day will attest.

Canvassing

I’m always conscious, when writing, of the responsibility to present a balanced view. Recently I’ve been using social media more and more to canvass the opinions of others (you can follow our Strengthening Practice Twitter account here and my professional Twitter account here). I’m very lucky to have a wide range of parents, carers, care-experienced people, and professionals from many backgrounds including social work, law, academia, education, health and policing around me on this media.

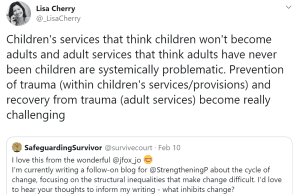

In early February, I asked what other people thought about change and what made it difficult. A few quotes really stood out.

This one by Lisa Cherry, a trainer and author on trauma, resonance and resilience, is probably something most of us could relate to. In my case, I was unwell enough to reach the threshold for child protection intervention, but not enough to reach the threshold to access adult services. Further probing on this issue lead to the same responses; it came down to resources and money.

But I’d go one further and say that the system itself is disjointed. This article by Community Care look at the statistics surrounding care leavers which are not often seen, the government statistics preferring instead to focus on things like employment, education and housing. The article talks about the research “Our Care, Our Lives” by the Bright Spots Programme, a partnership between Coram Voice and Professor Julie Selwyn. The study itself has developed a new set of care leaver well being indicators around what young people say is important to them: feeling settled, having trusted relationships, good worker support, access to the internet, having fun and a really good friend as well as knowing there is someone who believes in you are all included, and this is important. Without looking at the whole person and their whole experiences, how can we help someone to change their behaviours? If a care leaver is struggling with employment, simply giving them a job is not going to solve the problem. Surrounding them instead with a range of support to meet other, perhaps more hidden, needs, is more likely to yield sustained and motivated change. But of course, that comes down to money.

Another point which was well-made by social worker @msniklaus talked about religion and culture being a possible inhibitor to successful change. I confess to not thinking deeply about this until it was mentioned, simply because I have no religion and my culture is fairly standard white British. I think, in all honesty, these issues are not “on my radar” simply because they don’t tend to play a role in my life. And that’s quite wrong of me. I should be more aware of other people’s cultures and how they may then interact with the work that I’m doing. It made me wonder how many more of us are perhaps “guilty” of this, unwittingly and unknowingly.

Finally; this quote by Jo-Anne Welsh, a nurse and the CEO of Oasis, Brighton, captured my own experiences perfectly:

“Poverty? Hard to focus on behavioural change when you’re hungry…”

In conclusion, there’s much more to think about! The cycle of change is not linear, nor is it always within your reach. As a parent caught up in the child protection process, it can sometimes feel like the requirement to make changes is thrust upon you by people in a more sure-footed position than you. Practical support helps; sometimes it really does boil down to money and resources rather than simply “insight” and “determination”. But in order to sustain a change, you also need insight into your previous behaviours, a determination to succeed, a motivation to keep going and the tools to manage the impact of the change to give yourself the best chance of success. Most importantly, we need you, and those around us, to believe in our ability to change and sustain that change. We may never before have experienced someone believing in us. It cannot be our only succour, but it’s a pretty good place to start.

In conclusion, there’s much more to think about! The cycle of change is not linear, nor is it always within your reach. As a parent caught up in the child protection process, it can sometimes feel like the requirement to make changes is thrust upon you by people in a more sure-footed position than you. Practical support helps; sometimes it really does boil down to money and resources rather than simply “insight” and “determination”. But in order to sustain a change, you also need insight into your previous behaviours, a determination to succeed, a motivation to keep going and the tools to manage the impact of the change to give yourself the best chance of success. Most importantly, we need you, and those around us, to believe in our ability to change and sustain that change. We may never before have experienced someone believing in us. It cannot be our only succour, but it’s a pretty good place to start.

That, reader, is where you come in.

Thanks for reading.

Annie

Social Care Trainer

Strengthening Practice

Featured Image “Change” by Conal Gallagher on Flickr Creative Commons – thanks.